This weekend I was observing at the William Herschel Telescope at the Roque de los Muchachos observatory on La Palma, Canaria shown. You can see a picture of the telescope in figure 1 below. We were using the Long-slit Intermediate Resolution Infrared Spectrograph (LIRIS) instrument which can be used for both imaging and spectroscopy.

Figure 1. The William Herschel Telescope, La Palma, Canaria.

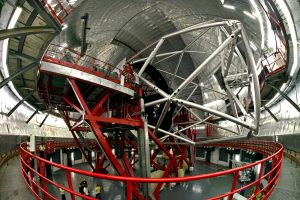

While at the top of the mountain I also had the chance to see the Gran Telescopio Canarias, the biggest telescope in the world. It was extremely impressive. What I found most remarkable is how easily it appears to move around. It weighs 400 tonnes but is so finely balanced that it can be turned by hand if necessary.

sFigure 2. Inside the Gran Telescopio Canarias.

Another highlight was seeing the Isaac Newton Telescope, first built in 1967 and operated at Herstmonceaux castle in Sussex which is historically related with the University of Sussex, where I was working until a few weeks ago. The telescope was then moved to La Palma when the bad English weather and seeing became limiting (I could have told them that would happen). This telescope had wooden interiors and a different kind of mounting which together showed how astronomy has changed over the last decades. The Isaac Newton Telescope uses an equatorial mount like the telescope I have used as an amateur hobbyist.

We were looking at lensed galaxies in the near infrared. A lensed galaxy is where a galaxy lies in front of another one and due to the effects of general relativity it ‘bends’ the light from the galaxy behind it and makes it look slightly brighter and a different shape than it would without the foreground galaxy being there. Figure 3 shows an extreme example imaged by the Hubble Space Telescope.

Figure 3. A strongly lensed galaxy in the Einstein ring configuration. These are rare and the lenses we were looking at were typically in an Einstein cross configuration.

This is part of a bigger project to look for interesting events in lensed galaxies that I will blog about later. We had a sample of these lenses that have been found in large area surveys of the sky. Imaging the objects is relatively simple. We set the telescope to look at the position of the object then check the image to see if we are looking at the right place. Typically the objects we are interested in are very faint so we need to look at nearby bright stars to check the position against a map of stars. Then we ‘integrate’ by taking large numbers of, for instance 30 second, exposures to be summed later in order to collect more photons over a larger time such as an hour. This allows us to observe extremely faint objects. Some of the objects we were looking at had a redshift greater than 2. This means the Universe has expanded by a factor of 3 (given by redshift plus one) since the galaxy emitted the photons we are measuring. The light from objects at that distance has travelled for around ten billion years to reach us.

This was my first observing run and there is clearly an enormous amount of expertise required to make good observations. One aspect that hadn’t occurred to me is that it is quite stressful. The telescope time is very valuable so you can’t be wasting time not taking measurements but trying to understand the telescope commands. Equally, it is vital to check that everything is working and the data is good. Those two concerns mean that you have to be quite alert and careful when setting up the runs. Afterwards you are typically just letting the telescope take measurements. At five in the morning these two things can be quite a challenge.

Seeing images of these distant galaxies fresh off the telescope reminded me how remarkable modern astronomy is and will keep me going through the long winter of tapping away at keyboards and moving numbers around on a screen.